First Previous Next Last

Contextualizing the Visual (and Virtual) Realities of Expo 2010

Susan R. Fernsebner

Images

Figure 15.1

Haibao, mascot of Expo 2010, welcomes visitors to the Pavilion of the Future. Haibao’s gender has been debated, though the consensus seems to be that Haibao is male. One official introduction categorizes Haibao as being of “a boyish character.” His hobbies are listed as “taking baths and dancing” while his favorite beverage is “coffee-tea,” said to help him maintain his energy for greeting exposition visitors. His height, in the same quick-facts introduction, is listed as “can be as high as he wants.”Source: Personal collection of Susan Fernsebner.

Figure 15.2

For the Chinese government the 2008 Beijing Olympics served as a bold prelude to the Shanghai World Expo, a successful first run at orchestrating an enormous media spectacle for global and domestic consumption. This image from Wikicommons captures the iconic Bird’s Nest stadium amid a shower of fireworks during the breath-taking opening ceremony. Images of the Beijing Olympics abound online, and would be worth comparing to those of the Shanghai Expo; for scholarly discussion of the Beijing Olympics see Further Readings.Source: Wikicommons

Figure 15.3

A screen capture from the Expo Online website that is still running as of March 2014 and provides further examples of “interactive” images and games.Figure 15.4

One of several corporate pavilions at the 2010 Expo, the Oil Pavilion was the site for the showing of the GM sponsored film discussed in this chapter.Source: Wikicommons

Figure 15.5

The Oil Baby online game from Expo 2010’s Oil Pavilion. Controls for home appliances areat the upper left, while recycling cans, and meters for consumption and conservancy are at the fore and right. The clean blue river, green lawn, and foliage indicate Oil Baby is carefully conserving at the moment, though important energy decisions await. From: .Source: http://www.cnpc.com.cn/syg/ssize/index.html [accessed 20 August 2011]

Figure 15.6

This pair of photographs (from Wikicommons, by Bobak) from August of 2005 in Beijing gives a sense of how severe air pollution can often be in many of China’s cities. Air pollution has become even more severe and widespread in Chinese cities over the last decade, and has become a top priority for the Chinese government and a central issue driving citizen protest. For excellent journalism and discussion on air pollution and other environmental issues facing China today in both English and Chinese languages (including links to hundreds of photographs) visit China Dialogue at https://www.chinadialogue.net/Source: Wikicommons

Figure 15.7

Satirical image of the heroic Zhang Fei competing for reserve tickets for Expo 2010. The webpage is well worth visiting for well over a dozen more such satirical images produced by Hong Kong bloggers.Source: http://www.zonaeuropa.com/20100505_1.htm [accessed 31 August 2011]

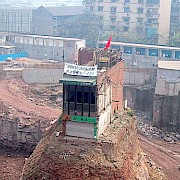

Figure 15.8

This is an image from Wikicommons of what became China’s most famous, and photogenic, “nail house” over the last decade. The term “nail house” (钉子户)is a recently invented Chinese word to describe buildings (usually homes) which the owners refuse to allow to be torn down despite a government mandates for new construction. The nail house pictured here was in the city of Chongqing at a site slated for the building of a shopping mall. Often the nail house residents have to stay physically in their homes for months or even years on end to prevent their demolition. “Nail houses” became one of the most visible symbols of popular protest against local and municipal governments’ opportunistic top-down control over land development. For more images of such “hold out architecture,” mainly from China see: http://io9.com/unbelievable-nail-houses-around-the-world-892781747 (accessed March 17, 2014)Source: Wikicommons

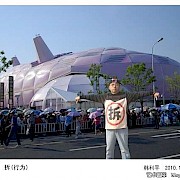

Figure 15.8b

In this image of protest art, the figure in the foreground is standing in front of a popular pavilion at the Shanghai Expo wearing a word that has become notorious over the last two decades in China : TEAR DOWN (Chai: 拆). Nail houses (see Figure 15.8) are just the most striking visual example of the waves of forced relocations that have been imposed upon tens of millions of households across China’s cities and villages over the last two decades. In almost all cases compensation (in forms of money payment and replacement housing) is offered, but the terms are often far below market rates, and there is often little dialogue with residents about the planning. In cities and towns throughout China, buildings slated for demolition are painted with the word 拆 to signal to wrecking crews (and the public) what buildings are to be torn down.Figure 15.9

A scene from Shanghai’s Pudong district amid demolition of older city neighborhoods in 2009. The freshly painted wall advertises next year’s coming Expo 2010 and its slogan, which was officially translated into English as “Better City, Better Life.”Source: Personal collection of Susan Fernsebner

Chapter Sample

In the months leading up to “Expo 2010 Shanghai,” the first official world’s fair to be held in China, advertisements for the event abounded. Promotional video created under the auspices of the Chinese Communist state declared the exposition a celebration of achievements in “urban civilization,” noting the theme of the event itself as “Better City, Better Life.” State promoters promised that the Expo would display the potential for a “harmonious coexistence between humans and nature in the cities of the future.”1 Meanwhile the official Expo mascot, a blue creature named "Haibao," promoted the coming event as a fun-filled spectacle in his2 own public appearances, video, and a serial television program (Figure 15.1). A Fall 2009 edition of the official Expo Shanghai Newsletter offers similar promotional rhetoric. The lead story notes that a city-wide tourism festival, “an entertainment extravaganza,” would take place in conjunction with Expo 2010, and attendees could purchase enticing multi-event ticket packages. Other articles in the newsletter note the Expo’s upcoming displays of Chinese jade “and its 8,000-year history” by a Taiwanese organization, as well as opportunity for all to appreciate the “grassland beauty” of Inner Mongolia that would be displayed at the fair. The same newsletter also heralds the upcoming “virtual Expo online” through which all individuals worldwide with access to the Internet could tour the halls of the exposition from the comfort of their very own home.3 This array of celebratory images for Expo 2010 advertises a greater China, including politically contested territories, as well as the new position held by the People’s Republic of China on a global stage.

The content of this publicity, moreover, is intricately linked to the evolving methods of its propagation. These methods include a potent mix of new and long-existent media, including print, television, digital media and Internet venues, and through these channels an overlap with state propaganda itself. Indeed, in Expo 2010’s imagery we find a grand-scale example of the Chinese Communist state’s adoption of corporate methods of advertising, particularly in the realm of visual culture, and the state’s own appropriation of popular culture and entertainment.4 As such, Expo 2010 provides an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Chinese state and its corporate partners have set forth publicity as a more subtle form of propaganda, and to investigate a related phenomenon, namely the relationship between state and popular images in Chinese social, cultural, and political discourse.

The Chinese state mobilized publicity for Expo 2010 as a symbol of China’s twenty-first century modernization. Much of this publicity was aimed directly at a Chinese domestic audience and shared not only via television and print periodicals, but also through the realm of “new media,” including websites, popular video pages, and social networking venues. Indeed, these venues were celebrated by the fair’s promoters, who heralded Expo 2010 as the first fully online world’s fair. Yet ironically, even as the state utilized the Internet to promote Expo 2010 and its own political message of “harmonious development,” the emergence of digital media itself also placed the ability to disseminate alternative images into the hands of millions of Chinese “netizens” (individuals using the Internet) to share their own commentary and critique.5 While the Chinese state seeks to mobilize and control a public discourse, ordinary people have mobilized similar tools to offer alternative presentations. Returning to a point made in this volume’s introduction, if the state seeks to “see” and control a citizenry, an examination of Expo 2010 and the new media accompanying it reveals that seeing is indeed a “two-way street.”

This chapter will explore the complexities of Expo 2010 and its broader social and political context through visual traces of the fair itself. These traces include images and video created by the event’s state and corporate sponsors as well as other images and scenes from diverse sites that summer. Indeed, there were–and still are–multiple realms for experiencing Expo 2010: not just the Expo fairgrounds and pavilion architecture, but also the surrounding city in which it was located, Shanghai. The three main sections that follow will offer historical background for the event and its conception, a close analysis of the visual evidence (including an online video game and a feature video drama) from two popular Expo pavilions, and finally a look at alternate images of the event, its impact on local communities, and its implications for the analysis of state-society relationships in China today.

1“Gala of World Civilization: World Expo 2010 Shanghai China” video presented at the official Expo 2010 Shanghai China website. http://en.expo2010.cn/documents/hqxcp.htm [accessed 9 September 2011]. For CCTV (China Central Television, a state-managed broadcast network) coverage of Expo 2010, including the opening ceremony, see the videos available at: http://www.cctv.com/english/special/expo/live/index.shtml [accessed 20 December, 2013].

2Or “her”—Haibao’s gender has been debated, though the consensus seems to be that Haibao is male. One official introduction categorizes Haibao’s gender as being of “a boyish character.” Haibao’s hobbies are listed as “taking baths and dancing” while his favorite beverage is “coffee-tea,” said to help him maintain his energy for greeting exposition visitors. His height, in the same quick-facts introduction, is listed as “can be as high as he wants.” See “Haibao Revealed in a Cartoon Series,” in the Shanghai Daily and its exposition supplement, “Expo Insight” (7 September 2009). http://en.expo2010.cn/pdf/insight/0907.pdf [accessed 17 September 2011].

3Expo Shanghai Newsletter, no. 32 (17 September 2009). http://en.expo2010.cn/pdf/newsletter/32.pdf [accessed 9 September 2011]. The basketball event also received significant television news coverage; see for example: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lnjX6QhZ6xo [accessed 20 December 2013] .

4For an exploration of this broader process, see Geremie R. Barmé, In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture (New York: Columbia UP, 1999), particularly “CCPTM & Adcult PRC,” 235–254.

5In July, 2011, the China Internet Network Information Center (CINIC) reported the number of Chinese Internet users as having reached 485 million. See CINIC, “Zhongguo hulian wangluo fazhan zhuangkuang tongji baogao,” http://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/201206/t20120612_26719.htm (accessed 20 December 2013).

Further Reading

Claypool, Lisa. "Zhang Jian and China's First Museum," Journal of Asian Studies 64, no. 3 (August 2005): 567-604.

Debord, Guy. Society of the Spectacle. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. New York: Zone Books, 1994.

Fernsebner, Susan R. "Objects, Spectacle, and a Nation on Display at the Nanyang Exposition of 1910." Late Imperial China 27.2 (December 2006): 99-124.

Mitchell, Timothy. Colonising Egypt. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991.

Study Questions

Images from Oil Baby online game from Expo 2010. Source: Expo 2010 Oil Pavilion website: http://www.cnpc.com.cn/syg/ssize/index.html [accessed on 20 August 2011] [dead link].

These are three images from different moments in a sequence of one round of play in the Oil Baby game. The outcome clearly is not the ideal one for the player. Yet the storyline is one of several intended by the game’s designers and advertised within the Oil Pavilion itself. As such, it also presents an opportunity for study.

In viewing the visual evidence from the frames above, consider the following questions:

- What do you see from the screen’s elements as components of the game? (Consider making a list). Key factors in the game that they may indicate? Goals, strategies, potential outcomes?

- What appear to be the main activities for the character on the screen?

- What kind of a social world does the realm represented within the four walls of this screen encompass?

- Who might the main audience for this game have been? Messages it might convey to an audience in the year 2010? Comparisons to the world in which they were (or are) already living?