First Previous Next Last

Spatial Profiling:

Seeing Rural and Urban in Mao’s China

Jeremy Brown

Images

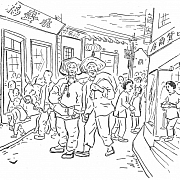

Figure 11.1

This cartoon comes from a travel montage featuring the Communists’ efforts to rebuild the city of Yantai in Shandong province in 1950. The cartoonist’s message was that peasant shoppers belonged in a healthy socialist city, but they were nonetheless clearly identified as wide-eyed, bumpkin-like outsiders. From: Shang Yi, “Nongminmen xiao mimi de jincheng lai mai dongxi” [Peasants smilingly enter the city to buy things], Manhua yuekan 6 (November 1, 1950): 20.Figure 11.2

Li Changjie, “Jiaoliu xuexi xinde” [Study notes on an exchange], Renmin huabao she. July 1968. In this photograph by a photographer working for China Pictorial (Renmin huabao), a model sent-down youth, Xing Yanzi, speaks with an unidentified woman, whose red ribbon reads “daibiao” (representative). Available from: ChinaFotoBank, photo 301644, http://photos.cipg.org.cn/.Figure 11.3

This visual depiction of urban-rural difference appears in a book of verse celebrating China’s “worker-peasant alliance” (gongnong lianmeng). From: Xiu Mengqian, Gongnong lianmeng xiang qian jin [The worker-peasant alliance advances forward] (Shanghai: Laodong chubanshe, 1953), 18.Figure 11.4

Gao Mingyi, “Hou Jun he qunzhong tantao tianjian guanli” [Hou Jun explores field management with the masses], Renmin huabao she. 1975. In this photograph by a photographer working for China Pictorial, model sent-down youth Hou Jun (front left), works in the fields with the nameless “masses” of Doujia village. Available from: ChinaFotoBank, photo 284385, http://photos.cipg.org.cn/.Figure 11.5

Preparing lunch in a village north of Tianjin in 2005. During the Mao period, rural people were amazed when they visited urbanites who used gas for cooking heat. Many villagers cooked by burning organic byproducts, and some continue to do so today. The stove in the center of this photograph visually marks this scene as rural. Photo copyright Laura Benson, February 12, 2005.Chapter Sample

People in all societies judge, categorize, and differentiate. During China’s socialist period (1949-1978), one of the main sites of differentiation and discrimination was place-based: urban versus rural. Like racial, ethnic, and gender difference in North America today, rural-urban difference in Mao Zedong’s China was socially constructed and historically contingent. But it was also very real. The way people saw and experienced rural-urban difference had real consequences. Under Mao, people who lived in villages ate different food, spoke a different language, wore different clothes, and had a different skin color from people who lived in cities. A peasant’s typical day was different from that of an urban worker. The economic gap was also huge: urban people earned guaranteed salaries and had money to spend while village incomes were miniscule and tenuous.

When we consider that the Communist revolution was based on peasant support and aimed to bridge the economic and cultural chasm separating city from village, it seems puzzling that difference between urban and rural people remained so persistent during the Mao era. According to orthodox Marxism, the countryside was backward and stagnant, and only the urban working class could effect revolutionary change. China under Mao, however, appeared to point toward a new path, with peasants as the main revolutionary force offering the utopian promise of equality between city and countryside. But reality was more complex. After the Communists established the People’s Republic in 1949, China entered a period of “learning from the Soviet Union” and Soviet-style heavy industrial development became priority number one.[1] In order to finance urban industrialization, peasants were forced to sell grain to the state at artificially low prices and were restricted from leaving their villages. At times, Mao expressed dismay at the anti-rural implications of this policy orientation. As historian Maurice Meisner writes, Mao responded by promoting the “resurgence of an ideology that spoke on the peasants’ behalf and the pursuit of policies that tended to benefit the countryside rather than the cities and their ‘urban overlords.’”[2] This ideology was most evident during the Great Leap Forward (1958-1960), which called for irrigation projects, rural electrification, and small-scale village industry, and again during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), when more rural youths attended school than at any other point in Chinese history.

Yet while the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution were ambitious and ultimately cataclysmic experiments, neither event significantly changed how rural and urban people saw each other. Why not? One significant factor was the two-tiered household registration, or hukou, system, which classified every individual in China according to rural or urban residence.[3] Household registration was institutionalized after the starvations and massive population dislocations of the Great Leap famine (when tens of millions perished), and it guaranteed food rations, housing, health care, and education to urban residents. Rural people were expected to be self-reliant and were officially restricted from moving to cities, although many peasants still migrated illicitly.[4] Mao may have periodically questioned the anti-rural nature of China’s Stalinist development model, but because he never wavered from its institutional underpinnings (the hukou system and grain rationing), rural and urban people remained unequal.

While scholars have documented the details and consequences of the hukou system, the visual dimension of rural-urban difference is less well understood. Rural-urban difference endured under Mao because of an ingrained culture of seeing that predated the Communist takeover of the mainland. I call this culture of seeing “spatial profiling,” which means determining someone’s background as rural or urban at first glance and treating him or her differently based on appearance. When we analyze place-based identity in China in terms of how people saw one another, everyday exchanges and local practices seem more powerful and lasting than Maoist ideology or shifting national policy.

[1] Research for this chapter was assisted by a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Award and a Social Science Research Council International Dissertation Field Research Fellowship with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For a concise overview of the planned economy under Mao, see Barry Naughton, The Chinese Economy: Transitions and Growth (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2007), 55-84.

[2] Maurice J. Meisner, Marxism, Maoism, and Utopianism: Eight Essays (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982), 71.

[3] Tiejun Cheng and Mark Selden, “The Origins and Consequences of China’s Hukou System,” China Quarterly 139 (September 1994): 644-668.

[4] On the substantial unsanctioned migration of the Mao period, see Diana Lary, “Hidden Migrations: Movements of Shandong People, 1949-1978,” Chinese Environment and Development 7, no. 1-2 (1996): 56-72.

Further Reading

Brown, Jeremy. City versus Countryside in Mao’s China: Negotiating the Divide. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Cho, Mun Young. The Specter of “The People”: Urban Poverty in Northeast China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013.

Han Han. "Why Do You Cost More Than Me?" In This Generation: Dispatches from China's Most Popular Literary Star (and Race-Car Driver). Alan H. Barr, ed. and trans, 5-8. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012.

Chang, Leslie T. Factory Girls: From Village to City in a Changing China. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2008.

Cheng, Tiejun and Mark Selden, “The Origins and Consequences of China’s Hukou System.” China Quarterly 139 (1994): 644–68.

Eyferth, Jacob. Eating Rice from Bamboo Roots: The Social History of a Community of Handicraft Papermakers in Rural Sichuan, 1920–2000. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2009.

Flower, John Myers. “Peasant Consciousness.” In Post-Socialist Peasant? Rural and Urban Constructions of Identity in Eastern Europe, East Asia, and the Former Soviet Union, edited by Pamela Leonard and Deema Kaneff, 44–72. New York: Palgrave, 2002.

Han, Xiaorong. Chinese Discourses on the Peasant, 1900–1949. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2005.

State Council. "Criteria for the Demarcation between Urban and Rural Areas." November 1955. In Cheng, Tiejun. “The Dialectics of Control—the Household Registration (Hukou) System in Contemporary China.” PhD diss., State University of New York at Binghamton, 1991, 399-400.

Zheng, Tiantian. Red Lights: The Lives of Sex Workers in Postsocialist China. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Study Questions

These questions can be explored without outside reading:

1. The spatial profiling described in Jeremy Brown's chapter is not what top Communist Party leaders intended to achieve with their policies. What do you think explains the divergence between intentions and results?

2. Think back to the last time you "profiled" someone based on their clothing, skin color, "bearing," or accent. In that moment, did you realize you were engaged in "profiling"? How do you think your own historical context affected your behavior and thoughts? How would your behavior and thinking have been different had you been born and raised in the Chinese context described in Brown's chapter?

For these questions, consult the "Further Readings" section:

1. In your classroom, work together with all of your classmates to make a line-up with the most "urban" students at one end of the room, the most "rural" ones at the other end, and everyone else in between. Use all of the criteria described in Brown's chapter, along with the State Council's "Criteria for the Demarcation between Urban and Rural Areas" from November 1955, to help determine where you fit in the line-up. After everyone is lined up, discuss as a group what you noticed about the exercise, how you negotiated with your classmates, and how you felt about your place in the line.

2. How is the rural-urban divide described by Han Han in his 2006 essay "Why do you cost more than me?" different from the gap described in Brown's chapter? How is it similar? How is the legacy of the Mao era relevant to the problems Han Han describes? Do you think Han Han's satirical approach is fruitful or counterproductive?

3. How is the spatial profiling carried out by urban residents and rural migrants in Harbin, described in chapters 5 and 6 of Mun Young Cho's book, different from the Mao-era spatial profiling analyzed in Brown's chapter? How is it similar? How does living in close proximity affect the relationship between urbanites and rural migrants?