First Previous Next Last

Images, Memories, and Lives of Sent-down Youth in Yunnan

Xiaowei Zheng

Images

Figure 1.9

This photograph, by a photographer of a brigade propaganda team in Yunnan, presents a happy image of sent-down youth laboring in the countryside. Today such images are often used to bolster the idea that former sent-down youth should have "no regrets" about their experiences.Source: Personal collection of Xie Guangzhi.

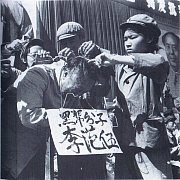

Figure 13.1

Red Guards attack provincial governor Li Fanwu. This photograph, by photojournalist Li Zhensheng, appears in his celebrated English-language book Red-Color News Soldier (London: Phaedon, 2003) and a web exhibit by the same name, and has toured museums throughout Europe and North America. It also appears in a popular U.S. textbook on modern Chinese history, Jonathan Spence’s The Search for Modern China (New York: Norton, 1999, plate between p. 662 and p. 663). Such images dominate representations of the Cultural Revolution for Western audiences and produce a very one-sided understanding of what the Cultural Revolution meant and how people experienced it.Source: Used with permission from Contact Press Images.

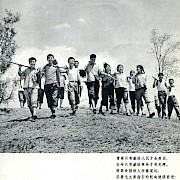

Figure 13.2

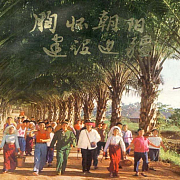

Sent-down youth joyfully labor in the countryside. This photograph originally appeared in a Cultural Revolution pictorial. The caption beneath reads, "Youth is beautiful only when it is dedicated to the people; Life is bright only when it is dedicated to the revolution; It is a heavy burden and a long journey to become a worthy revolutionary successor; We will move forward following the course directed by Chairman Mao." Former sent-down youth Xie Guangzhi remembers offering to put the photograph on display for a 1991 exhibition on sent-down youth held in the Sichuan Provincial Museum in Chengdu. Such images, produced during the Cultural Revolution and recirculated in later years, present a much more optimistic – though still very one-sided – view of how youth experienced the Cultural Revolution. Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.Figure 13.3

"Xionghuai zhaoyang; Jianshe bianjiang" [With a Heart Full of Passion, Construct the Frontier]. This is the cover page of a popular pictorial compiled by the Office of Sent-Down Youth Affiliated to the Revolutionary Committee of Yunnan Province. The pictorial was published in January of 1973. Yunnan is portrayed as a beautiful, rich, and fertile place where the PLA soldiers, sent-down youth, and various local minority people happily work together. The pictorial contains another twenty-two photographs and pictures portraying sent-down youth’s life in Yunnan: they are all smiling and well taken care of. The pictorial had a big impact on some of the people interviewed for this chapter. Xu Shifu, for example, clearly remembered the photographs in this pictorial and said that they helped create a false image of Yunnan for him. Source: Office of Sent-Down Youth Affiliated to the Revolutionary Committee of Yunnan Province ed., "Xionghuai zhaoyang; Jianshe bianjiang" [With a Heart Full of Passion, Construct the Chinese Frontier], (Yunnan Renmin chubanshe, Kunming: 1973), front cover.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi.

Figure 13.4

Paper-cut by a sent-down youth depicting a group of Wa nationality women dancing. Sent-down youth frequently turned to art, sports, or other recreation to find some meaning outside the political struggles and hard labor that dominated their lives in the countryside. For this sent-down youth, Yunnan's ethnic minority cultures appeared to offer a refreshing contrast with Cultural Revolution politics. Paper-cut by Zhang Qingcong.Source: Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Figure 13.5

In 1978 and 1979, sent-down youth in Yunnan staged protests in order to draw political attention to their situations, with the hope that they would be allowed to return to their urban homes. This image depicts sent-down youth swearing an oath to continue a hunger strike. The photograph, taken by a sent-down youth from Shanghai, offers a strikingly different window into how youth experienced the Cultural Revolution from those presented in Figures 13.1 and 13.2. Here, youth are active historical agents pursuing their own agenda.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

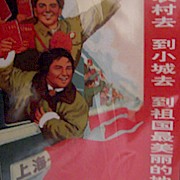

Figure 13.6

"Dao nongcun qu, dao xiaocheng qu, dao zuguo zui meili de difang qu" [Go to the Countryside, Go to the Small Cities, Go to Our Motherland’s Most Beautiful Places]. This is a typical propaganda poster circulating in early 1970s China.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

Figure 13.7

"Zuoqing zhibian heying liunian" [Family Photograph before Zuoqing Left for the Border Area]. This photograph was taken before a sent-down youth named Zuoqing (the girl in the middle of the second row) was sent to Yunnan. Zuoqing came from the City of Chengdu and she was sent to Yunnan in June of 1971. Provided by Yang Quan and used with his permission.Source: Provided by Yang Quan and used with his permission.

Figure 13.8

"Huanying zhiqing lai chang" [Welcoming Sent-Down Youth Coming to the Farm]. Taken by a photographer of a brigade propaganda team in Yunnan, this photograph portrays a welcoming scene: old sent-downers welcoming new comers to a Yunnan farm.Source: Provided by Yang Quan and used with his permission.

Figure 13.9

"Yuan ershi qituan siying shilian" [The Former Tenth Company of the Fourth Battalion of the Seventh Regiment of the Second Division]. In Yunnan, all sent-down youth were considered PLA soldiers and were militarily managed. This photograph was taken by Yang Quan, a former sent-down youth of the Tenth Company, who came back to look for his old bungalow.Source: Provided by Yang Quan and used with his permission.

Figure 13.10

Female Sent-Down Youth/ Female Soldiers. Taken by a photographer of a brigade propaganda team in Yunnan, this photograph presents the notion that sent-down youth were also proud PLA soldiers.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

Figure 13.11

PLA Captains Teaching Sent-Down Girls to Hold Rifles. Taken by a photographer of a brigade propaganda team in Yunnan, this photograph presents a harmonious relationship between the PLA soldiers and the sent-down youth in Yunnan.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

Figure 13.12

Looking Afar. Taken by a photographer of a brigade propaganda team in Yunnan, this photograph presents the notion that sent-down youth were also proud PLA soldiers.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

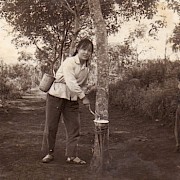

Figure 13.13

Draining Rubber Sap. This is a beautiful photograph that makes laboring look poetic. A local propaganda team took this photograph. According to Xie Guangzhi, every single battalion, regiment and division in the Yunnan Construction Corps supported a propaganda team that actively produced photographs. Despite the food deficiency in Yunnan, the propaganda team was equipped with a camera and rolls of film to produce these photographs.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

Figure 13.14

Draining Rubber Sap. Taken by by a photographer of a brigade propaganda team in Yunnan, this photo presents a light-hearted image of sent-down youth laboring in the countryside.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

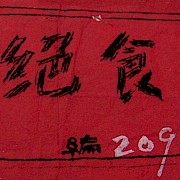

Figure 13.15

"Jueshi: Bianhao 209" [Hunger Strike: Badge No. 209]. This and the following four images all relate to the hunger strike depicted in Figure 13.5 and explored fully in the book chapter. This is the badge that a hunger striker used during the strike. The badge has been carefully kept by the striker to this day.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

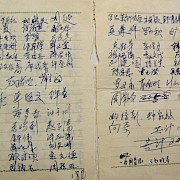

Figure 13.16

Name List of the Hunger Strikers. Altogether 211 people participated in the hunger strike. They signed their names before going into the iron gate. Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

Figure 13.17

Hunger Strike Scene: Two Girls. This photograph was taken by a sent-down youth who stood outside the iron gate. After years of saving, he had finally been able to afford an expensive camera for his own use. He shot four rolls of films of the hunger strike scene and managed to save thirty-six pictures, of which this is one.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

Figure 13.18

Hunger Strike Scene: Doctors Waiting On the Side. This is another of the thirty-six hunger strike pictures the photographer preserved.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

Figure 13.19

Hunger Strike Scene: Zhao Fan Talking to the Sent-Down Youth. This is another of the thirty-six hunger strike pictures.Source: Provided by Xie Guangzhi and used with his permission.

Figure 13.20

Sketch by Zhang Qingcong of an old man of Dai ethnicity. This is another of Zhang’s creations during his Yunnan years (see Figure 13.4). Using pens, pencils, and scissors, Zhang avidly recorded the beauty around him. In creating a world of his own, his felt his life became meaningful.Source: Provided by Zhang Qingcong and used with his permission.

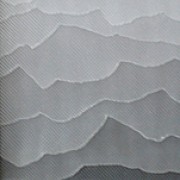

Figure 13.21

Zhang Qingcong showed Zheng Xiaowei this piece in 2006 during an interview. Zhang created it in the mid-1990s to express his feelings about Yunnan. To Zhang, Yunnan is a paradox much more complicated than the one-dimensional story in the "no-regret" account. He remembers Yunnan’s beautiful mountains and continues to dream about them: this piece is meant to capture those dreams. However, Zhang also remembers his Yunnan years as gloomy and solemn, and that is why, he explains, he used the color grey to finish the piece.Source: Provided by Zhang Qingcong and used with his permission.

Chapter Sample

In 2006, I lived in the city of Chengdu in southwestern Sichuan Province. My apartment was about a mile west of downtown, in a building off a small alleyway. The alley was noisy during the day and quiet at night, much like any other urban residential area in China. At first, there seemed to be nothing special about it. However, as time passed, an unusual teahouse caught my eye. Set in a three-room condo on the first floor of a building about a hundred meters from where I lived, this teahouse was always bustling. Almost every night, a group of middle-aged men and women congregated, chatting away about household chores, reading evening newspapers, and playing Mahjong.

Like most Chinese cities, Chengdu is changing fast—state-owned factories laying off workers, suburban farmers losing their land, and house prices skyrocketing far past what an ordinary resident could easily afford. The teahouse regulars are just like their fellow Chengdu residents, striving hard to make a living and survive the changes. They are among the most ordinary of people. Without asking, I would never have known who they were—that all of them as teenagers had packed their suitcases, left home, and spent eight precious years on a rubber farm in the border region of Yunnan Province. They were just some of the vast number of urban people sent to the countryside over the course of the Mao era (see Brown’s chapter in this volume). More specifically, they were among the twenty million middle school and high school graduates sent to the countryside for reeducation between 1968 and 1979, and still more specifically, among the one-hundred and forty thousand who worked in the Yunnan Construction Corps on China’s southern border.i Having negligible power or status, their past is of little interest to their neighbors, siblings, or even their children. In this highly pragmatic city, few people pay attention to their history; only in this little teahouse do they have a place to recollect the past and share some old memories.

The people I met in the teahouse all belong to a special generation in the history of the People’s Republic of China. Born between 1947 and 1955, they have experienced a life trajectory marked by sharp ups and downs closely tied to Chinese politics. In 1966, when Mao sought to reinvigorate China’s revolutionary culture and curb the influence of Liu Shaoqi and other “moderates” among the party leadership, he turned to China’s youth to be vanguards of the newly conceived “Cultural Revolution.” Many urban youth jumped at the chance to become “Red Guards.” When the Red Guards were disbanded in 1968, some of these same youth responded enthusiastically to Chairman Mao’s call to join the “Up to the Mountains, Down to the Countryside” movement and rushed to settle in China’s rural areas, where they were to learn from the peasants and put their schooling to work for China’s “new socialist countryside.” Others resisted the call but found themselves compelled nonetheless by a state anxious both to find occupations for a boom generation of urban youth and to quell the extensive havoc, no matter how “revolutionary,” the Red Guards had wreaked in the cities. The majority of them did not return to the cities until the late 1970s, having “lost” their youth and needing to cope with a now-unfamiliar urban life.

I had the good fortune to make friends with some of these former “sent-down youth” (the standard term for young, urban people sent to the countryside) and talk with them in depth about their experiences. They have generously shared their memories with me and provided me with precious photos, sketches, paintings, and posters that they have carefully kept from the Yunnan years. These artifacts not only help visualize the stories they tell, but also offer a serious challenge to the one-dimensional picture that prevails in the dominant narratives about the lives of sent-down youth. The tales they relate in the teashop also speak in compelling ways to the role that visual images play in producing history and memory. In this essay, I seek to answer the questions: How do people remember the Up to the Mountains, Down to the Countryside movement? What role do visual materials play in depicting the lives of sent-down youth? How do these most ordinary sent-down youth reflect upon and come to terms with their past, and, how do these memories interact with their lives today?

i Deng Xian, Zhongguo zhiqing meng [Dreams of Chinese Sent-down Youth] (Beijing: Remin wenxue chubanshe, 1993), 22 and 79.

Further Reading

Cao, Zuoya. Out of the Crucible: Literary Works about the Rusticated Youth. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2003.

Andrews, Julia F. and Xiaomei Chen, ed. Visual Culture and Memory in Modern China. A special issue of Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 12.2 (Fall 2000).

Chang, Jung. Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China. London: Simon and Schuster, 1991.

Esherick, Joseph W, Paul G. Pickowicz, and Andrew G. Walder, eds. The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006.

Evans, Harriet and Stephanie Donald, eds. Picturing Power in the People’s Republic of China: Posters of the Cultural Revolution. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1999.

Liang, Heng and Judith Shapiro. Son of the Revolution. New York: Knopf, 1983.

Zheng Wang, Xueping Zhong, and Bai Di, eds. Some of Us: Chinese Women Growing Up in the Mao Era. Piscataway: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Yang, Rae. Spider Eaters: A Memoir. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Yang, Bin. “‘We Want to Go Home!’ The Great Petition of the Zhiqing, Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, 1978–1979.” The China Quarterly 198 (June 2009): 401–421.

Ye Weili and Ma Xiaodong. Growing Up in the People’s Republic: Conversations between Two Daughters of China’s Revolution. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005.

Study Questions

Study Questions:

1. In this chapter, Xiaowei Zheng compares several competing narratives used to remember the Cultural Revolution, particularly as expressed through images. To what extent do the narratives presented in these images reflect the authors who created them? How does the context of the place and time they were created impact these images? Who is the intended audience?

2. Compare the images of female sent-down youth in this chapter to the "voyeuristic" pictures of young female athletes in Chapter 6. What similarities and differences do you see in terms of pose, dress, and attitude? What do you think accounts for the differences?

3. Some of these photographs are clearly staged. How does this impact their reliability? How does this impact their usefulness to historians?

4. How do the cheerful pictures of sent-down youth leaving home, arriving at their work sites, working, and participating in military exercises compare to the accounts of these events given by Zheng's interviewees?

Questions related to Further Reading:

1. In Some of Us: Chinese Women Growing Up in the Mao Era, Chinese women write of their experiences growing up during the Cultural Revolution. How do the stories in their memoirs compare to the narratives presented in this chapter? Many of the memoirs deal with the changing roles and expectations of women during the Cultural Revolution. Can you find evidence of these changes in the pictures from this chapter?

2. Zheng attempts to escape the trend of existing literature on the “Up to the Mountains, Down to the Countryside” movement by presenting sent-down youth as active agents in their own lives, rather than as passive subjects. How do the essays in The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History contribute to this project? What other examples can you find of ordinary people actively resisting or collaborating with agents of the state? To what extent were Chinese people during the Cultural Revolution able to determine their own destiny?

3. Zheng provides many images of sent-down youth and directs our attention to the narratives behind them. How can other images from the Cultural Revolution, such as the posters in Picturing Power in the People's Republic, assist in understanding this period? Do they seem to support similar narratives? How else might you interpret these images?