First Previous Next Last

Envisioning the Spectacle of Emperor Qianlong’s Tours of Southern China:

An Exercise in Historical Imagination

Michael Chang

Images

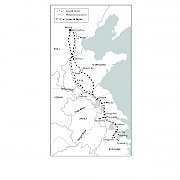

Figure 2.1

The Lower Yangtze River delta (or Jiangnan), including the emperor’s imperial route and the Grand Canal.Source: Stephanie R. Hurter, George Mason University Center for History and New Media. Used with permission.

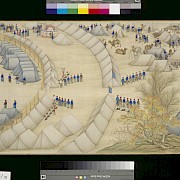

Figure 2.2

River crossings like that seen here reveal some of the complicated, but often overlooked, logistics involved in transforming the Qing court into a mobile entity.Source: Nie, ed., Qing Dynasty Court Paintings (Qing dai gongting huihua) (Hong Kong: The Commercial Press, 1996), 17.

Figure 2.3

A portrait of Joohoi in full battle armor. Joohoi was one of the commanders of the Imperial Escorts for Qianlong’s earliest southern tours as well as a highly-decorated and experienced field commander and expert in military supply who saw frontline action in Qianlong’s famed “Western Campaigns” (1755-1759).Source: Palace Museum, Beijing.

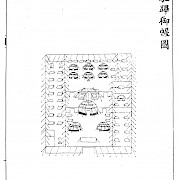

Figure 2.4

Main imperial encampment which was used during imperial hunts and during other imperial tours of inspection, but which does not appear in the court paintings of the Qianlong emperor’s southern tours.Source: Illustrations of the Qing Huidian (Qing huidian tu, c. 1899) (reprint Beijing: Zhonghua shuju 1991), v. 1, p. 1026, juan 104, 3a-b.

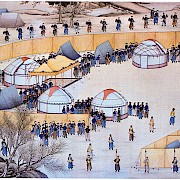

Figure 2.5

The “yellow perimeter” (huangcheng) defined the core of the camp, the emperor’s personal quarters, including Mongolian ger (a.k.a. “yurts”).Source: Illustrations of the Qing Huidian, v. 1, p. 1027, juan 104, 6a.

Figure 2.6

One hundred seventy-five simple pup-tents (or “officials’ tents” zhiguan zhangfang).Source: Illustrations of the Qing Huidian, v. 1, p. 1034, juan 105, 2a.

Figure 2.7

Detachments of imperial bodyguards stood as sentries at the various camp entrances.Source: Reunion de Musees Nationaux.

Figure 2.8

Giuseppe Castiglione’s “Gathering for a Meal during the Hunt,” which prominently features Mongolian ger (or “yurts”).Source: Qing Dynasty Court Paintings, p. 164

Figure 2.9

“Imperial Banquet in the Garden of Ten-Thousand Trees,” which also prominently features Mongolian ger (or “yurts”).Source: Qing Dynasty Court Paintings, p.172-73.

Figure 2.10

This is a less schematic picture of an encampment in which we see some ger (yurts) and the bunting that was used for the yellow perimeter.Source: Bi Meixue (Michele Pirazzoli-t'Serstevens) and Hou Jinlang, Illustrations of Mulan and Studies of Qianlong's Annual Autumn Hunts (Mulan tu yu Qianlong qiuji dalie zhi yanjiu) (Taibei: Guoli gugong bowuyuan, 1982),. color plate no.4.

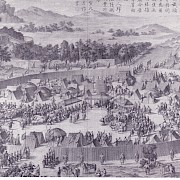

Figure 2.11

Qing commanders received the surrender of the Beg of Ush in 1758 in a military encampment that clearly resembled the encampments used during imperial hunts and during other imperial tours of inspection, such as the Qianlong emperor’s southern tours to the Lower Yangtze delta.Source: Taipei National Palace Museum.

Figure 2.13

A detail from the first scroll of the Kangxi era southern tour paintings, which shows two camels with collapsed yurts packed on their backs.Source: Qing Dynasty Court Paintings, p. 10-11.

Figure 2.14

Intermediate day camp (jianying, dunying, or wu-dun; Manchu: uden-I ba), where the emperor and his guards would rest and take midday meals and which resembled the hunting camp depicted in Figure 2.8.Source: Illustrations of the Qing Huidian, v. 1, p. 1028, juan 104, 8a.

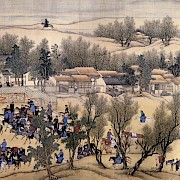

Figure 2.15

The Qianlong Emperor's Entry into Suzhou in 1751, featuring the emperor on horseback surrounded by his most loyal and stalwart Manchu and Mongolian troops. Here one may note that the figure of the Qianlong emperor is slightly larger in size and stares directly at the viewer of the painting. By Xu Yang, Qianlong nanxun tu juan 乾隆南巡圖卷, c. 1770 (scroll six detail).

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, with permission.

Figure 2.16

Qianlong engaging in the Battue Hunt, also featuring the emperor on horseback surrounded by his most loyal and stalwart Manchu and Mongolian troops. By Ignatius Sichelbarth (Ai Qimeng), Qianlong congbo xingwei tuzhu 乾隆叢薄行圍圖軸.

Source: Qing Dynasty Court Paintings, 196.

Figure 2.17

The Qianlong Emperor's Entry into Jehol, also featuring the emperor on horseback surrounded by his most loyal and stalwart Manchu and Mongolian troops. By Giuseppe Castiglione, Mulan tu juan 木蘭圖, c. 1750s (scroll one detail)

Source: Illustrations of Mulan and Studies of Qianlong's Annual Autumn Hunts, p. 184.

Chapter Sample

A picture’s worth a thousand words. The camera does not lie. Seeing is believing. Such are the deeply ingrained platitudes of our own historically situated ways of seeing, shaped by an age of mechanical reproduction and mass mediated visual culture. But what are we, as critically minded students of history, to make of the visual evidence we encounter in our romps through the archives and in our everyday lives? If historical imagination is also a visual exercise, how are we to envision the past(s) that we study and attempt to know? This paper addresses such questions by focusing on the well-known southern tours of the Qianlong emperor (1711-1799, r. 1736-1795), the fourth Manchu emperor to rule over China proper.

Each of Qianlong’s six southern tours, which took place between 1751 and 1784,[i] were extended affairs, during which the emperor and his rather sizeable entourage spent anywhere from three to five months traveling through one of the empire’s most prosperous and critical regions—the Lower Yangtze delta (Jiangnan). “Jiangnan” literally means “south of the (Yangtze) River,” but actually refers to a more broadly defined geo-cultural region straddling the boundary of two key provinces: Jiangsu and Zhejiang. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, these two provinces were vital to the Qing empire in a number of ways.[ii] Politically, Han Chinese literati from Jiangsu and Zhejiang comprised the majority of officials who staffed the lower echelons of the civil administration. Economically, these two provinces generated the bulk of the empire’s commercial and agricultural wealth, supplying it with surplus (tribute) grain and the lion’s share of tax revenues, not to mention other critical staples and luxury items such as salt, silk, and porcelain. Culturally, Jiangnan was not only the undisputed center of Han literati scholarship and refinement, but also, from the Qing conquest in the mid-seventeenth century onward, a bastion of Ming loyalism and anti-Manchu sentiment.

Qianlong engaged in a wide range of other activities on his visits to the Lower Yangtze region. He inspected hydraulic infrastructure, presented obeisance to local deities, evaluated local officials, held audiences with local notables, showered individual officials and subjects with imperial favor and recognition, recruited scholarly and literary talents, conducted military reviews, visited scenic and historic sites, and even received tribal envoys from Inner Asia.

But what did a southern tour actually look like? Such deceptively simple questions provide the starting points of most historical inquiry; they are born of a certain degree of ignorance, which is a necessary precondition of curiosity. The answers at which we arrive depend upon our capacity to both critically evaluate and creatively interpret the range of perspectives offered by sources at hand. In the pages that follow, we will consider a variety of sources including court paintings, imperial poetry, literati accounts, administrative regulations, and archival documents. By reading this wide array of sources in conjunction with and against each other, we may conclude, somewhat counter-intuitively and paradoxically, that the court paintings of the Qianlong emperor’s southern tours, while helpful in many respects, do not necessarily provide us with a complete picture (pardon the pun) of those spectacular events.

Further Reading

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books, 1972 (1990 reprint edition).

Beurdeley, Cécile and Michel. Giuseppe Castiglione: A Jesuit Painter at the Court of the Chinese Emperors. Translated by Michael Bullock. Rutland VT and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1971.

Chang, Michael G. A Court on Horseback: Imperial Touring and the Construction of Qing Rule, 1680-1785. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2007.

Clunas, Craig. Art in China. 2nd edition. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Introduction, pp. 9-13.

- "Early Qing Court Art" and "The Qianlong Reign," pp. 72-84.

Elliott, Mark C. Emperor Qianlong: Son of Heaven, Man of the World. New York: Longman, 2009.

Hearn, Maxwell K. "Document and Portrait: The Southern Tour Paintings of Kangxi and Qianlong." Phoebus 6.1 (1988): 91-131.

McDermott Joseph P. “Introduction.” In Joseph P. McDermott, ed. State and Court Ritual in China, pp. 1-19. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Perdue, Peter C. "Military Mobilization in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century China, Russia, and Mongolia." Modern Asian Studies 30.4 (October 1996): 757-793.

Rawski, Evelyn S. and Rawson, Jessica, eds. China: the Three Emperors, 1662-1795. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2005.

Recording the Grandeur of the Qing: the Southern Inspection Tour Scrolls of the Kangxi and Qianlong Emperors. http://www.learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu/start.html

-a collaborative project of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Asia for Educators Program at Columbia University, and the Visual Media Center at Columbia University (2005).

Symons, Van J. "Qianlong on the Road: The Imperial Tours to Chengde." In James A. Millward, Ruth W. Dunnell, Mark C. Elliott, and Philippe Forêt, eds. New Qing Imperial History: the Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde, pp. 55-65. New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004.

Waley-Cohen, Joanna. "Commemorating War in Eighteenth-Century China." Modern Asian Studies 30.4 (October 1996): 869-899.

Waley-Cohen, Joanna. "Military Ritual and the Qing Empire." In Nicola di Cosmo, ed. Warfare in Inner Asian History (500-1800), pp. 405-444. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

Study Questions

These questions can be explored without outside reading:

1. In this chapter, Michael Chang explores the role and place of Qing era court paintings as a primary source upon which we might rely to imagine and visually reconstruct what one of the Qianlong emperor’s “southern tours” looked like. Why is the use of court paintings alone problematic in Chang’s view? And what additional types of primary sources does Chang rely upon to make his argument?

2. Compare the efforts to establish the Qing court’s authority detailed in this chapter to the efforts found in Chapter 5 (“Monumentality in Nationalist Nanjing: Purple Mountain’s Changing Views” by Charles Musgrove), which details how architecture and public spectacles were also used to promote “republican monumentalism” in the 1920s. What similarities and differences do you find between the eighteenth century and the early-twentieth century? What has changed? What has remained the same? What might shifts in visual technologies and methods of disseminating visual images tell us about changes in the nature of politics during these two vastly different time periods?

For these questions, consult the "Further Readings" section:

1. In his influential book, Ways of Seeing, John Berger writes, “The relationship between what we see and what we know is never settled.” What does Berger mean by this? And how does Chang’s argument about court paintings and their relationship to actual practices of imperial touring relate to Berger’s point?

2. In his discussion of Qing-era court paintings, Chang raises the issue of who was actually in charge of executing various types of projects. In particular, he makes a distinction between the types of paintings for which Chinese literati might be responsible and others for which Jesuit painters serving at court might be responsible. Can you find any evidence for a content-related “division-of-labor” between Chinese literati painters and Jesuit painters by looking at the works by Cécile and Michel Beurdeley, Craig Clunas, Maxwell Hearn, Evelyn Rawski and Jessica Rawson as well as the website Recording the Grandeur of the Qing?

3. How did the martial and implicitly ethnic dimensions of the Qianlong emperor’s southern tours explored in this chapter relate to the broader historical changes taking place during the mid- to late-eighteenth centuries? See especially Elliott’s Emperor Qianlong, Perdue’s “Military Mobilization in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century China, Russia, and Mongolia,” as well as Waley-Cohen’s “Commemorating War in Eighteenth-Century China” and “Military Ritual and the Qing Empire.”