First Previous Next Last

"The Me in the Mirror":

A Narrative of Voyeurism and Discipline in Chinese Women’s Physical Culture, 1921-1937

Andrew Morris

Images

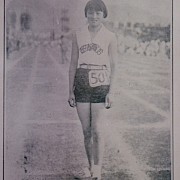

Figure 6.1

Sun Guiyun, women’s track and field individual champion, Fifteenth North China Games, as pictured in the official meet program. The photographer seems to have positioned Sun, China’s first female athletic star, as a figure purely of the present, set apart from a mythologized “history” of Chinese women’s weakness. Sun’s posture is demure and modest, though at the time her sleeveless uniform and short shorts would have made this a very revealing photo. Five years later, writers would condemn Sun for leaving behind this early “timidity, shyness and naivete” for a “magnificent and luxurious wardrobe. . . [and] makeup.” Di shiwu jie Huabei yundonghui [The Fifteenth North China Games] (n.p., 1931), n.p.Figure 6.2

Shenbao quanguo yundonghui jinian tekan (The Shun Pao All-China Olympic Special Edition) (Shanghai: Shenbao, 1933), front cover.Figure 6.3

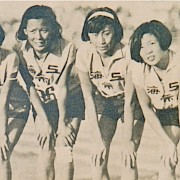

Shanghai women’s 400-meter relay team, 1933 National Games. Ershier nian Quanguo yundong dahui choubei weiyuanhui, eds., Ershier nian Quanguo yundong dahui zongbaogao shu [1933 National Games Official Report] (Shanghai: Zhonghua shuju, 1934), n.p.Figure 6.4

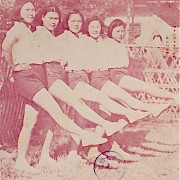

Hong Kong women swimmers, including the “Beautiful Mermaid” Yang Xiuqiong at center, Fifth National Games, 1933. This was a common type of photograph in sporting magazines; it not only accentuated these women’s individual beauty and physiques in a very revealing way but also situated this within a context of teamwork, solidarity, and cooperation—the values that modern sport was meant to inculcate in Chinese citizens of the 1930s. Qinfen tiyu yuebao [Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly] 3.1 (October 1935), front cover.Figure 6.5

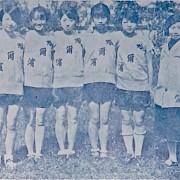

Harbin women athletes, Fourth National Games, 1930, as pictured in a Shanghai-published meet pictorial. This photo is another example of the sporting values of teamwork, cooperation, and solidarity combined with a “gaze” toward young women’s bodies. Quanguo yundonghui tuhua zhuankan (The Fourth “National Atheletic Meet”) (Shanghai: Liangyou tushu yinshua gongsi, 1930), p. 11Figure 6.6

Students of East Asia Physical Education School, Shanghai, as portrayed on the cover of Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly. Young women’s physical fitness and expertise was almost always portrayed (in what would have been considered at the time) sexualized displays of the body. These young women’s facial expressions suggest that they did not feel comfortable participating in this sexualized pose of the bodies that they were dedicating years to training and strengthening for very different reasons. Qinfen tiyu yuebao [Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly] 2.7 (April 1935), front cover detailFigure 6.7

Liaoning women’s tennis team, Fourth National Games, 1930, as pictured in a Shanghai-published meet pictorial. Though positioned at the side of the photo, the male coach of this team in many ways dominated this image—although the poses struck by these young women from Liaoning also suggest that they did not feel themselves to be of secondary importance in this enterprise. Their very “preppy” uniforms also remind the viewer of the importance of socioeconomic class in the Republican-era world of modern sports. Quanguo yundonghui tuhua zhuankan, p. 33Figure 6.8

Tianjin women athletes, Fourth National Games, 1930, as pictured in a Shanghai-published meet pictorial. This image is dominated in a similar way by the male team leader, despite his position at the edge of the frame. The presence of authoritative men as coach was meant to maintain sport as a realm acceptable to national and modern prerogatives, and to mitigate against the “dangers” posed to society by newly social and sexual mobile young women. Quanguo yundonghui tuhua zhuankan, p. 11.Figure 6.9

The Harbin track athletes (including Sun Guiyun at lower left) famed as the “Four Harbin Sisters” and the “Four Healthy Women Generals” (nü jian jiang), as pictured in the official Fifteenth North China Games program in 1931. Their photogenic quality won them much attention, although the nature of this attention changed as these women matured and followed different paths in their adult lives. By 1935 this earlier intimate discourse of praise had quickly transformed into one of judgmental sexual innuendo and condemnation. Di shiwu jie Huabei yundonghui, n.pFigure 1.5

(See Introduction). The swimming He sisters of Qingdao— Wenya, Wenjing and Wenjin—who became nationally known with their sweep of all women’s swimming events at the Eighteenth North China Swim Meet in 1934. These young women also seem less than comfortable participating in a sexualized swimsuit pose that both emphasized the female strength and athleticism needed by the nation and as well as accommodated the “male gaze” toward commodified female bodies. Qingdao shi Tiyu xiejinhui, Liang zhounian gongzuo zongbaogao [Two Year Anniversary Official Work Report] (Qingdao: Qingdao Tiyu xiejinhui chuban weiyuanhui, 1935), n.pFigure 6.10

Hong Kong swimmer Yang Xiuqiong, “The Beautiful Mermaid.” Zhonghua yuebao (The Central China Monthly) 3.10 (October 1935), back coverFigure 6.11

Figure X.11. Caption reads: “Two hemispheres—fair and black. The American jumper, Miss Poynton-Hill, and the Chinese swimmer, Miss Young Sau-king [Yang Xiuqiong] at Berlin.” The racist photo caption could only have been lifted from a Western publication seemingly incredulous that the “black” Eastern hemisphere could produce female athletes of Yang’s quality. The Chinese context of this photo would have been very nearly the exact opposite, however. This photo proudly positioned Yang as an example of female beauty, sexuality, modernity, and strength inferior to no one, “even” a blonde American Olympic medalist like Poynton-Hill. “Ladies at the XI Olympiad,” The Illustrated Week-End Sporting World (Jingle huabao) 10.62 (19 September 1936), p. 7Figure 6.12

Figures 6.12 and 6.13. Hong Kong swimming sensation Yang Xiuqiong, as pictured (at left) in the “Sweaters” section, and on her own individual page, of a Shanghai-published program for the Fifth National Games in 1933. The teenaged Yang, the most famed and photographed of all of 1930s China’s athletes, was known as “The Beautiful Mermaid” and “Miss China.” However, her typically accommodating nature and her embrace of her role also made her the subject of much sexualized innuendo and rumor. The “good girl” image created by the media was, after all, very simply the mirror image of the type of the “bad girl” whose modern beauty, participation in this public realm, and willingness to pose in revealing swimsuits could only lead her and other young women down dangerous and immoral paths in modern China. Minguo ershier nian Quanguo yundonghui zhuankan (National Athletic Meet Special 1933) (Shanghai: Shidai tushu gongsi, 1933), n.p.Figure 6.14

Enlarged inset of Figure X.14. Here we see Yang Xiuqiong as the constant center of photographers’ attention, daily being asked to stand smiling and nearly naked in front of black whirring machines and the tops of these men’s heads. The “photo of the photographers” composition was also a common one, as it established this technology as a key element of this intersection between sport, fitness, nationalism, entertainment, and prurience. Minguo ershier nian Quanguo yundonghui zhuankan, n.p.Figure 6.15

“The two female heroes of Qingdao martial arts,” Jiang Ailan at left and Luan Xiuyun (with tiger-head hook sword) at right. Luan, who taught martial arts in two Qingdao elementary schools, as well as at her own First Women’s Martial Arts Training Center, was judged by city sports authorities in 1935 to be “the perfect female athletic figure.” The more conservative clothing associated with martial arts and the fact that martial arts, though being explicitly modernized at this moment in Republican China, were imagined to be a more “traditional” realm that modern/Western sport, meant that women participating in this field of physical endeavor simply were not part of the same sexualizing, commodifying, and moralizing discourses as were their female sprinter or swimmer counterparts. Qingdao shi Tiyu xiejinhui, Liang zhounian gongzuo zongbaogao, n.p.Figure 6.16

Deng Yinjiao and Chen Jian, “the two female heroes of Malayan Chinese track and field,” at the Sixth National Games, held in Shanghai in 1935. Several of the Chinese National Games featured teams of ethnic Chinese athletes from abroad, as part of the project to imagine “national” ties between citizens of the Republic of China and Overseas Chinese all over the world. Deng (left) set a “national” record in the long jump, but as the main text notes, was better known to readers of the 1936 Roll of Famous Chinese Women Athletes for her possession of—if not a “beautiful” face or “silvery” skin—then at least a healthy, beautiful figure. Chen (right) led the Malayan Chinese track and field team to a silver medal at these National Games. Qinfen tiyu yuebao [Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly] 3.2 (November 1935), front cover detail.Figure 6.17

A Miss Liu of the Guangdong Province Swim Team, Sixth National Games, 1935. This type of photo, which took advantage of the very revealing qualities of a wet swimsuit but (thinly) veiled its prurience by using the discourse of healthy women’s bodies and their value to the nation, was common in sporting magazines of the time. Zhonghua yuebao (The Central China Monthly) 3.11 (November 1935), n.p.Figure 6.18

Photos from the women’s volleyball demonstration event, China vs. Japan, Sixth Far Eastern Championship Games, Osaka, 1923. The very loose-fitting tops, bloomers, and beanies that these women wore, which were very typical costume for women athletes in the West as well at this time, did not captivate media attention the way that the revealing uniforms just a few years later did. Fünu zazhi (The Ladies’ Journal) 9.8 (August 1923), n.p.Figure 6.19

Men and women of the Shandong track and field team, Fifteenth North China Games, 1931. Team pictures often were composed in this way, with a front row of women sitting below their male teammates, their legs bared and extended toward the camera’s gaze. The groups of men and women are both represented as coherent teams, but the female athletes seem in this photo to be infantilized and to occupy a less developed form of athleticism, teamwork, and strength. Di shiwu jie Huabei yundonghui, n.p.Figure 6.20

The Hong Kong swim team, Fifth National Games, Nanjing, 1933. As in Figure 6.19, many team photos were composed so as to display women’s “healthy-beautiful” physiques more prominently than those of their male teammates. Qinfen tiyu yuebao [Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly] 1.2 (November 1933), n.p.Figure 6.21

These students at the Shanghai Patriotic Girls’ School were posed straddling a set of parallel bars for the cover of Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly’s January 1935 issue. The young women toward the foreground seem to be uncomfortable in this gratuitous pose, as they perhaps wondered just how revealing these photos had to be to establish their fitness as modern Chinese citizens. Qinfen tiyu yuebao [Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly] 2.4 (January 1935), cover photo.Figure 6.22

Swimmer Yang Xiuqiong at the Nanchang New Life Club, where Yang put on a swimming demonstration in 1934 in support of the Nationalist Party’s “New Life” anti-communist movement. The Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly reporter on hand quickly shifted the topic of his dispatch from “curing China’s poverty and weakness” to “[Yang] Xiuqiong’s developed body.” Yang’s expression here again reminds us about the uncomfortable costs of becoming a female sports icon under the media’s gaze. was taken at the Nanchang New Life Club, where Yang put on a swimming demonstration in 1934 in support of the New Life anti-communist movement. Tellingly, the Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly reporter on hand began his dispatch by testifying to this movement’s centrality in “curing China’s poverty and weakness,” only to become preoccupied with “Xiuqiong’s developed body,” and concluding simply that “this is why [the title] Miss China belongs to her.” (Yiru, “Jiangxi shuishang yundonghui,” pp. 27-28.) The photo itself clearly did not represent a “Mermaid” moment, but did the wet swimsuit and all it revealed compensate for this flaw? Qinfen tiyu yuebao [Diligent Struggle Sport Monthly] 1.11 (August 1934), n.p.Chapter Sample

In 1931, a Shanghai woman named Dai Mengqin wrote a short article for The Life Weekly on her recent conversion to a healthy exercise-filled life. Dai opened her piece by providing “historical background” that employed modern stereotypes of Chinese women’s essential and unchanging weakness:

Our nation’s women have always sat around, just keeping an eye on the home, and not being accustomed to movement. Except for women working in the fields, they all were practically just Lin Daiyu [the female protagonist of Dream of the Red Chamber, famed for her weak feminine beauty], possessing beautiful features but lacking a healthy body.[i]

Dai described how she personally exacerbated this already sorry heritage by dismissing her husband’s positive ideas about exercise. It was not until Dai examined in this same Life Weekly magazine some of its frequent “Healthy and Beautiful” pictorials, that she saw the light:

I started to understand that a body’s features and look are not unchangeable, that one can use one’s own power to change oneself. My soul was extremely moved. That night I went to a bookstore and bought an American sports magazine, and after reading through it I realized that my interest was growing even stronger. I decided that I would learn how to exercise. The next day I bought a swimsuit and came back home to put it on before a mirror. I looked like a woman with a healthy body, but upon closer examination I noticed some major faults: (1) I had too much body fat, (2) my thighs were too thick, (3) my chest was too skinny, (4) my arms were a little bit too large.

Determined to correct these faults, Dai began practicing sixteen types of exercise that her husband taught her. Enthusiastic about this modern technology of the self,[ii] Dai explained how she always took this exercise while “examining myself in the mirror. The me in the mirror is like my companion, and also like my strict teacher.”[iii]

Chinese women’s physical culture during the Republican era (1912-1949), and especially during the prewar 1930s, presents a very complicated historical problem. Women, especially urban women like Dai, were objectified more and more by three main forces: a conservative and reactionary morality (purportedly “Confucian” but actually very modern), an invasive and exploitative media, and the crisis mentality of a government staring down the barrel of imminent war with the Japanese. The world of sport and physical culture (tiyu) can serve as a perfect microcosm of the pressures and demands placed on certain members of Chinese society during this era.[iv] Others have written about the liberating aspects of athletic activity for women in China;[v] however, this is only one part of the story.

[i] Dai Mengqin, “Jianshen jianguo de tujing” [The Way to Build a Healthy Body and a Healthy Nation], Shenghuo zhoukan [The Life Weekly] 6.26 (20 June 1931), p. 535.

[ii] Foucault uses this phrase to discuss regimes of self-examination, obedience, and sacrifice of the self. Michel Foucault, et al., Technologies of the Self: A Seminar With Michel Foucault (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), p. 45.

[iii] Dai Mengqin, pp. 535-536.

[iv] On this topic, see two important recent books: Yunxiang Gao, Sporting Gender: Women Athletes and Celebrity-Making During China’s National Crisis, 1931-45 (Vancouver, B.C.: University of British Columbia Press, 2013); Yu Chien-ming, Yundongchang neiwai: Jindai Huadong diqu de nüzi tiyu (1895-1937) (On and Off the Playing Fields: A Modern History of Physical Education for Girls in Eastern China [1895-1937]) (Taipei: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, 2009).

[v] For example, see Fan Hong, Footbinding, Feminism and Freedom: The Liberation of Women’s Bodies in Modern China (Ilford, Essex: Frank Cass Publishers, 1997).

Further Reading

Chang, Michael G. “The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful: Movie Actresses and Public Discourse in Shanghai, 1920s-1930s.” In Yingjin Zhang, ed. Cinema and Urban Culture in Shanghai, 1922-1943, pp. 128-159. Stanford University Press, 1999.

Chow, Rey. Woman and Chinese Modernity: The Politics of Reading Between West and East. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991.

Dong, Madeleine Y. “Who Is Afraid of the Modern Girl?” In The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group, eds. The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization, pp. 194-219. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

Fan Hong. Footbinding, Feminism and Freedom: The Liberation of Women’s Bodies in Modern China. Ilford, Essex: Frank Cass Publishers, 1997.

Fujitani, Takashi. “Technologies of Power in Modern Japan: The Military, The ‘Local’, the Body.” Shisô 845 (November 1994).

Gao, Yunxiang. Sporting Gender: Women Athletes and Celebrity-Making During China’s National Crisis, 1931-45. Vancouver, B.C.: University of British Columbia Press, 2013.

Morris, Andrew. Marrow of the Nation: A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Study Questions

These questions can be explored without outside reading:

1. In this chapter, Andrew Morris details the highly voyeuristic aspect that pervades many of the images of young sports women in the Chinese pictorial press of the Republican era. Could we also use other historical lenses to read these images? How, for instance, might some of these images be analyzed if one were looking for symbols and evidence of modernization? Or nationalism? Or economic class?

2. Compare the evidence in this chapter to that found in Chapter 8 (“The Myth about Chinese Leftist Cinema” by Zhiwei Xiao), which highlights the tensions that arose around images of female bodies and sexuality in movies during this time period. What similarities and differences do you find?

2. All the images in Chapter 6 are of young women—there are no older women or clear images of mothers in these pictures. Indeed, if you look over pictures of women in calendar posters (like image 6.2), film stars etc. you will find a similar focus on women as young, single, healthy. and beautiful. What questions might this representational trend raise for us when we think about gender, women’s social roles, and/or the media in Republican era China?

For these questions, consult the "Further Readings" section:

1. Morris provides a wealth of images of young Chinese sportswomen in the Republican era. How is your understanding enriched through consideration of other materials that speak to the women's lives and experiences? For example, in Sporting Gender, how do Yunxiang Gao’s descriptions of sports women's lives and activities complement the overview Morris offers through the medium of visual culture?

2. While Morris focuses his analysis on how male voyeurism presented challenges and limitations to a newly emerging group of young sportswomen, women were becoming far more visible in a wide array of other Chinese urban venues and media in this era: on film and on stage, in magazines and in department stores, from dance halls to business offices. Their often highly fashionable and publicized images upset a lot of "conservative" and "Confucian" social values that emphasized the importance of women staying in the domestic sphere and keeping themselves and their bodies out of the public eye. Chang's "The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful," Chow's Woman and Chinese Modernity, and Dong's "Who Is Afraid of the Modern Girl" all explore another side to this male voyeurism: male anxiety. How do these phenomena coexist and inter-relate?

3. How did the gendering of sportswomen explored in this chapter fit into the larger history of Republican China’s sports culture? See especially Gao's Sporting Gender and Morris's Marrow of the Nation.