First Previous Next Last

Rethinking “China”:

Overseas Chinese and China’s Modernity

James A. Cook

Images

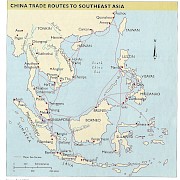

Figure 7.1

This map shows the trade routes of overseas Chinese merchants throughout Southeast Asia. Maritime trade connected the ports of Amoy, Quanzhou, and Guangzhou to the majors cities of Southeast Asia and these eventually became major population centers for Chinese abroad.Source: Anthony Reid, “Flows and Seepages in the Long-term Chinese Interaction with Southeast Asia,” in Sojourners and Settlers: Histories of Southeast Asia and the Chinese, eds. Anthony Reid and Kristine Ailunas-Rodgers (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1996), 16. Used with permission.

Figure 7.2

This map gives us an idea of the overseas Chinese populations living across the globe. Please note that Taiwan and Hong Kong are separated from China as a result of colonialism. What caused large numbers of Chinese to journey abroad and relocate in these countries? How do these significant numbers of Chinese living abroad force us to rethink what are the borders of China proper? Do we need to redefine the idea of “China”?Source: Map by Michael Lien. Used with permission.

Figure 7.3

This is a photograph of the current Mazu statue sitting in the Thian Hock Keng Temple. Although the statue is new, the hopes and aspirations found within the statuary are not. It is located in Singapore, but the statue is distinctly Chinese. What are the markers that tell us that this is a statue created for Chinese worshippers?Source: Used with permission.

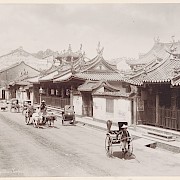

Figure 7.4

This is a picture of the Thian Hock Keng temple from the late nineteenth century shows the distinctively Chinese architecture of the temple. How do the numerous dragons and the architecture set it off as a distinctively Chinese space that is separated from the rest of the surrounding city?Source: Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board. Used with permission.

Chapter Sample

At a 1922 meeting of the Manila Chinese Chamber of Commerce, the “Cotton King” of the Philippines, the overseas Chinese entrepreneur Lin Zhuguang, gave a speech to his fellow Chamber members to announce a large gift he was making to build a primary school in his ancestral village located in the southeastern province of Fujian. Still only 21 years of age, Lin’s gift had taken the Chinese émigré community in Manila by storm. Philanthropy of this sort was supposed to be conducted by community elders; his father, Lin Xuedi, had given US$5,000 to disaster relief just before his death in 1918. For a young man like Lin Zhuguang to give a gift of such size caused quite a stir in the large, but close-knit Chinese business community of Manila.1

Part of the motivation behind Lin Zhuguang’s gift was to honor his father’s death, but other factors were also in play. “While honoring my father was certainly part of my intentions,” noted Lin, “I also want to use the gift as an opportunity to increase the influence of the overseas Chinese community back at home. We have a duty to our motherland to transform her as we have transformed Southeast Asia. What we have learned here must also beapplied in our villages and schools back at home.”2These patriotic motives continued to grow in the younger Lin. In later years, although he would continue to reside in Manila, he would contribute US$5,000 annually for the school’s upkeep and was a member of its board of directors. Why would Lin Zhuguang contribute so lavishly to a school located over 800 miles from his residence in Manila?

The answer to this question illustrates many of the ways in which living abroad affected the lives of China’s large overseas community. Life outside China not only made a great number of émigrés extremely wealthy, but also forced them to face virulent anti-Chinese racism, thereby creating within overseas Chinese communities a strong nationalism and a deep loyalty to Chinese culture. By the 1930s, these feelings had developed into a powerful desire to help rebuild and modernize their mother country. As one poet from Fujian Province who was living abroad noted:

Fujian is our ancestral village,

It feels like our blood and bones,

We are like its parents,

Protecting its shore and nurturing its growth.3

The process by which these feeling grew was both global and transnational in nature. Motivated by events both in China and abroad, many Chinese overseas like Lin Zhuguang played a critical role in communities on both sides of the ocean. Indeed, the economic and cultural contributions of Chinese abroad became so important that beginning in early-twentieth century the Chinese government coined a new term, Huaqiao or “Chinese sojourner,” to emphasize the permanence of Chinese citizenship. This new identity of the Huaqiao would transform the way in which many overseas Chinese imagined the Chinese nation, extending the country’s influence far beyond the geographical confines of China proper to include all residents in Chinese communities abroad.

The experiences of China’s Huaqiao in the twentieth century force us to rethink some of our most commonly held notions about the relationship between a nation, its territory, and its people. It has become second-nature for us to assume that the borders of a nation are conterminous with the geographical confines of its territory, and that only those who were born within or live within a nation’s borders are its citizens. The familiar map of China—the rooster-shaped outline whose head is Manchuria, chest is the southeast coast, and tail is the western provinces—certainly serves as an important visual representation of the nation. However, the rapid movement of Chinese sojourners back and forth across the Pacific to both North America and Southeast Asia, the development of Chinese communities abroad that have identified with the Chinese mainland rather than their host countries, and the rise of Chinese nationalism within those communities all attest to the fact that national boundaries may not be as fixed as we generally assume. What does it mean to live abroad but to still consider yourself to be Chinese? Can a nation be defined solely by territorial boarders, or can it be imagined socially, ethnically, or culturally?

The idea of remaining “Chinese” while abroad was reinforced by both cultural and geopolitical considerations emanating from both sides of the sea. Overseas Chinese continued to feel the magnetic pull of the homeland. They wove together an embracement of Chinese language, dress, diet, and customs with residence outside China into an identity that stressed the connection between Chinese culture and nationalism: they saw themselves as Huaqiao. If we emphasize a cultural identity rather than a national, as many Chinese living abroad did in the first half of the twentieth century, then our map of “China” may need to be redrawn.

This chapter analyzes the key visual images and markers that connected Huaqiao with China in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Like Charles Musgrove’s work on the structure of the Sun Yat-sen memorial located in the hills of Nanjing, it considers the meaning infused into important cultural and religious buildings, but moves to explore places—like Singapore, Batavia (Jakarta), and Saigon—outside the Chinese nation itself. These structures housed powerful reminders of the connection between Chinese immigrants and their hometowns. Temples, native place associations, and even homes were more than just buildings; they were concrete representations of the cultural and social forces around which émigré life was organized. Image, identity, and place were powerful forces connecting émigré Chinese and their hometowns in China, and they were steeped into the very structures that sheltered the overseas Chinese community. Eventually, these currents of culture and identity would also return to China and have a powerful impact on its own development.

1Xiamen huaqiao zhi bianzuan weiyuan hui, Xiamen huaqiao zhi (Xiamen: Lujiang chuban she, 1991), 354.

2Zhonghua shanghui chuban weiyuanhui, Feilubin Minlila Zhonghua shanghui sanshi zhou nian jinian li, 1904–1933 (Manila: Chinese Chamber of Commerce, 1936), ji yi.

3Zhu Ming, “Fujian shi women de jiaxiang,” Fujian yu huaqiao1.1 (April 1938), 17.

Further Reading

Cook, James A. “Re-Imagining China: Xiamen, Overseas Chinese, and a Transnational Modernity.” In Materializing Modernity: Changes in Everyday Life in Twentieth Century China, edited by Yue Dong and Joshua Goldstein, 156-194. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Frost, Mark R. and Yu-Mei Balasingamchow. Singapore: A Biography. Singapore: Didier Millet, 2009.

Hsu, Madeline Y. Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration Between the United States and South China, 1882-1943. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000.

McKeown, Adam. Chinese Migrant Networks and Cultural Change: Peru, Chicago and Hawaii, 1900-1936. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Pan, Lynn. Sons of the Yellow Emperor: A History of the Chinese Diaspora. New York: Kodansha, 1990.

Study Questions

These questions can be explored without outside reading:

1) As the 20th century progressed, Overseas Chinese or Huaqiao were able to move back and forth across the South China Sea with increasing speed and ease. Many had wives, families, and relatives in both China and Southeast Asia. The essay asks if a “nation” can be conceived not as a discrete geographical unit, but as a shared cultural or ethnic identity? What is your opinion? Does the presence of a highly mobile population destabilize national borders? What new opportunities are created?

2) Compare and contrast the images of the Thian Hock Keng temple in Singapore with the Sun Yat-sen memorial in the Musgrove chapter. Who was the audience that each structure was designed to serve? What symbolic or cultural markers define each of the buildings? One is built inside of China, the other outside of China, what differences in the visual signals do we see?

3) The shophouse in both Xiamen and Singapore came to symbolize the close connection between Overseas Chinese society and colonial economies. Why? Furthermore, why did the shophouse rather than the factory become an icon?

For these questions, consult the "Further Readings" section:

1) In his work on Hawaii, Chicago, and Peru, Adam McKeown analyzes transnational Chinese societies in places other than Southeast Asia. Review Overseas Chinese society in each of these other locations and compare them to what was presented in this essay? What similarities and differences exist between the different locales? What factors caused difference and what energies created similarities?

2) In analyzing Thian Hock Keng and the Sun Yat-sen mausoleum on the outskirts of Nanjing you analyzed public buildings and the messages they wanted to convey. What messages do our own religious and public sites, both national and local, convey?